Writing in Math Class: Why It’s Important and How We Can Help

Rusty Bresser

Writer William Zinsser once said that “writing is how we think our way into a subject and make it our own (1988, p. 16).” This quote resonates with me because when I write, I must think about what I know about whatever it is I am trying to learn. Writing helps me clarify my ideas and cement my understanding of what I’m learning. This is especially true for kids when it comes to math.

When students write about their math ideas, they use language in a variety of ways, whether they are describing a sequence of steps they’ve used to solve a problem, explaining a strategy for a logic game, comparing different polygons, or making predictions about a pattern they notice. Writing helps them think about their own thinking, thereby deepening their understanding of what they are learning.

Writing also provides a window into students’ thinking when we analyze their work. While diagrams and equations can help tell the story, words bring a strategy to life, giving us details that help us notice strengths or detect misconceptions, and ultimately guide our instruction to further student learning.

What Does Effective Math Writing Look Like?

Writing is hard! It can be especially difficult when you’re writing about math. Explaining a mathematical process requires the writer to be clear and logical. And math has a specialized vocabulary that must be used correctly to communicate ideas accurately. Because writing in math class is so important but can be so challenging (especially for English language learners), students may require lots of help.

To provide support, it’s helpful to know what effective math writing looks like. When writing about their thinking, effective writers:

- Use precise math language: vocabulary and descriptions

- Are clear and concise (teachers can understand how the student solved a problem or used a strategy)

- Make a claim (provide an answer)

- Support their claim with an explanation that’s logical and/or sequential

- Answer all parts of a math question

- Include labels to tell what the quantities mean

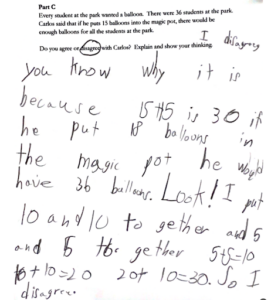

In this second grader’s written response to a prompt about dropping balloons into a magic doubling pot, notice how they make a claim and clearly explain their thinking process.

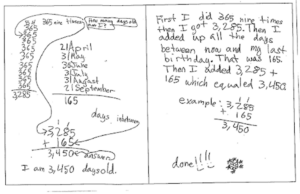

The following fifth grader explains how she figured out how many days old she is. She makes a claim, clearly and sequentially explains how she arrived at her answer, and labels what the numbers mean.

In the middle school sample below, the student solved a problem about whether there would be enough room for all the lunch tables in a space with given dimensions. They make a claim and provide evidence in a logical, sequential order, using precise math vocabulary and connecting words to help the reader navigate the explanation: “There will not be . . . I figured it out by . . .What I did was . . . then . . . I found that out by . . . Since ___ is bigger than ____, then . . . that means that . . .”

There will not be enough space for all the tables to fit in the lunch area. I figured this out by finding out the area of the lunch area. What I did was that I multiplied 20 feet by 24 feet and the answer was 480 square feet total in the lunch area. I then figured out how much space the tables took up. I found that out by multiplying the 32 lunch tables by 16 square feet which is the amount of space the tables took up. The answer to that problem was 512 square feet of space. Since 512 square feet is bigger than 480 square feet that means that the tables would not fit into the lunch area. The difference is 32 square feet. This means we’re missing 32 square feet in the lunch area to fit all of the lunch tables. We would only be able to fit 30 lunch tables.

For very young children, using numbers and pictures is the precursor for writing. This kindergartner clearly shows many ways 5 frogs can be on the log and in the pool. The next step would be to elicit an oral explanation from the student and perhaps take dictation so that they can see the connection to written words.

6 Ways Teachers Can Help

1. Pre-Writing: Discuss ideas before writing them down

Students may need to talk about their thinking in chunks before writing. Notice in the following scenario how the teacher supports the student by asking questions and rephrasing.

Teacher: “How did you estimate how many miles Lily’s mom traveled in a week?”

Student: “I rounded each number.”

Teacher: “To the nearest hundred or to the nearest ten?”

Student: “Hundred.”

Teacher: “So, to figure out how many miles, you rounded each number to the nearest hundred. Now write that down (if writing is still challenging, take dictation so that the student can see how writing and speaking are connected).”

Teacher: “Then what did you do?”

Student: “I added the rounded miles together.”

Teacher: Now write that down.

2. Model your own writing

Students benefit from seeing what writing about math looks like. For example, after a number talk, a teacher can choose one of the strategies a student has shared and write down the steps on the board for the problem, using the structure First, Next and Finally for 29+12:

Student strategy Teacher writes:

20+10=30 First, I added twenty plus ten and that equals thirty.

9+2=11 Next, I added nine plus two and that equals eleven.

30+11=41 Finally, I added thirty plus eleven and that equals forty-one.

3. Practice Interactive Writing

Interactive writing is where the teacher works with the rest of the class to craft an explanation (or part of an explanation) for a solution strategy. During interactive writing, the teacher can ask questions that prompt students to share ideas as the teacher models the writing process, thereby helping students think like expert writers.

-

How can we get started?

-

What would be a good claim to make?

-

What could we write to support our claim?

-

What evidence can we provide?

-

How can we make sure the reader understands what the numbers mean?

-

Do our ideas follow in a logical way?

-

Let’s re-read our writing to see if we want to make any adjustments.

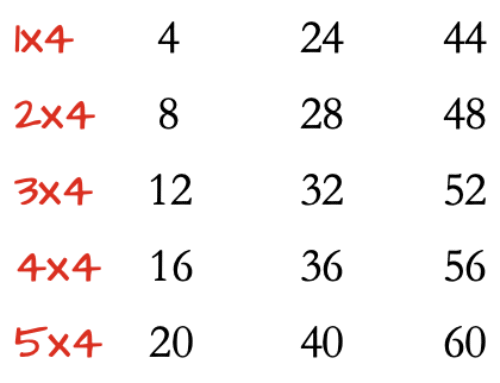

4. Provide vocabulary charts

Math has a specialized vocabulary that students will need to access and use when writing. Post these academic terms on a class chart along with context-related words (words related to the problem) so that students can access them when writing. Better yet, accompany each word with an illustration or symbol.

5. Make available sentence frames and starters

These supports can jump start the writing process for all students, but especially English learners. Frames and sentence starters can also help writers organize and frame their thoughts so that their writing is clear and makes sense. Choosing the best scaffolds will depend on the problem being solved. Here are some examples:

-

I think the answer is ____ because _______________.

-

First, I ______. Next, I ______. Then I _______. Finally, I _________.

-

I predict that_________.

-

If ________, then_______________.

-

To check my answer, I ______________.

-

I figured the answer out by __________________.

-

I agree/disagree because _________________.

-

____ therefore, ______________.

6. Provide Feedback Using Exemplars

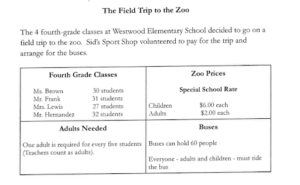

Effective feedback can help students improve their writing, especially if it’s specific and focuses on both the writer’s strengths as well as areas for growth. For example, fourth graders in Lakeside, California were given the following performance task.

Students had to figure out how many students and adults would go on the trip, how much the trip cost, and how many buses would be needed. They had to write a letter to Sid’s Sport Shop and let Sid know the cost and number of buses needed. Here’s one student’s response, followed by the teacher’s feedback:

Areas of Strength: “Your written explanation makes it easy for me to understand how you figured the total cost of the trip.”

Question: “I wonder why you added $6.00 plus $2.00 and then multiplied 8 x 144 to find the total cost of the trip.”

Areas for Growth: “I agree that there will be 120 students and 24 adults, and that 3 buses will be needed. How did you figure out that 3 buses will be needed? Please explain.”

Interactive Student Work Analysis

Teachers can give feedback, but they can also include their students in the feedback process. Imagine a group of third graders huddled on the rug as their teacher shows them a piece of work from another class. The following example represents a third grader’s attempt to show how they figured out how many dinners Sid the cat ate in one week if Sid ate six dinners each day.

The teacher begins the feedback session by asking the class, “What strengths do you see in the work? How does the writing help you understand how the student solved the problem?”

After a brief discussion, the teacher asks students if they have any advice that would improve the student’s writing. These feedback sessions can help students with their own writing because they get a chance to see good writing samples and they learn what they can do to improve their writing in math class.

Make Writing and Explaining a Routine Expectation

We are reminded of the importance of written explanations when we see how much it is emphasized within the California Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice (California Board of Education 2013) and when we read about the demands for strong communication skills arising out of a survey of current employers (National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2023).

In the classroom, we know that writing can deepen students’ understanding of math, and writing can help teachers assess what students know and what they still need to learn. But writing in math class is challenging. Students not only need targeted support and feedback, but they also need consistent opportunities to practice writing.

When we set the expectation that students will explain their reasoning and jot down how they solve a problem, this expectation becomes part of the classroom culture. Students will begin to expect the teacher to require them to explain, justify, and write down those thoughts, whether they are correct or incorrect. This daily practice will go a long way in helping students improve their writing, strengthen their problem-solving skills, and “think their way into mathematics and make it their own.”